- 1/1

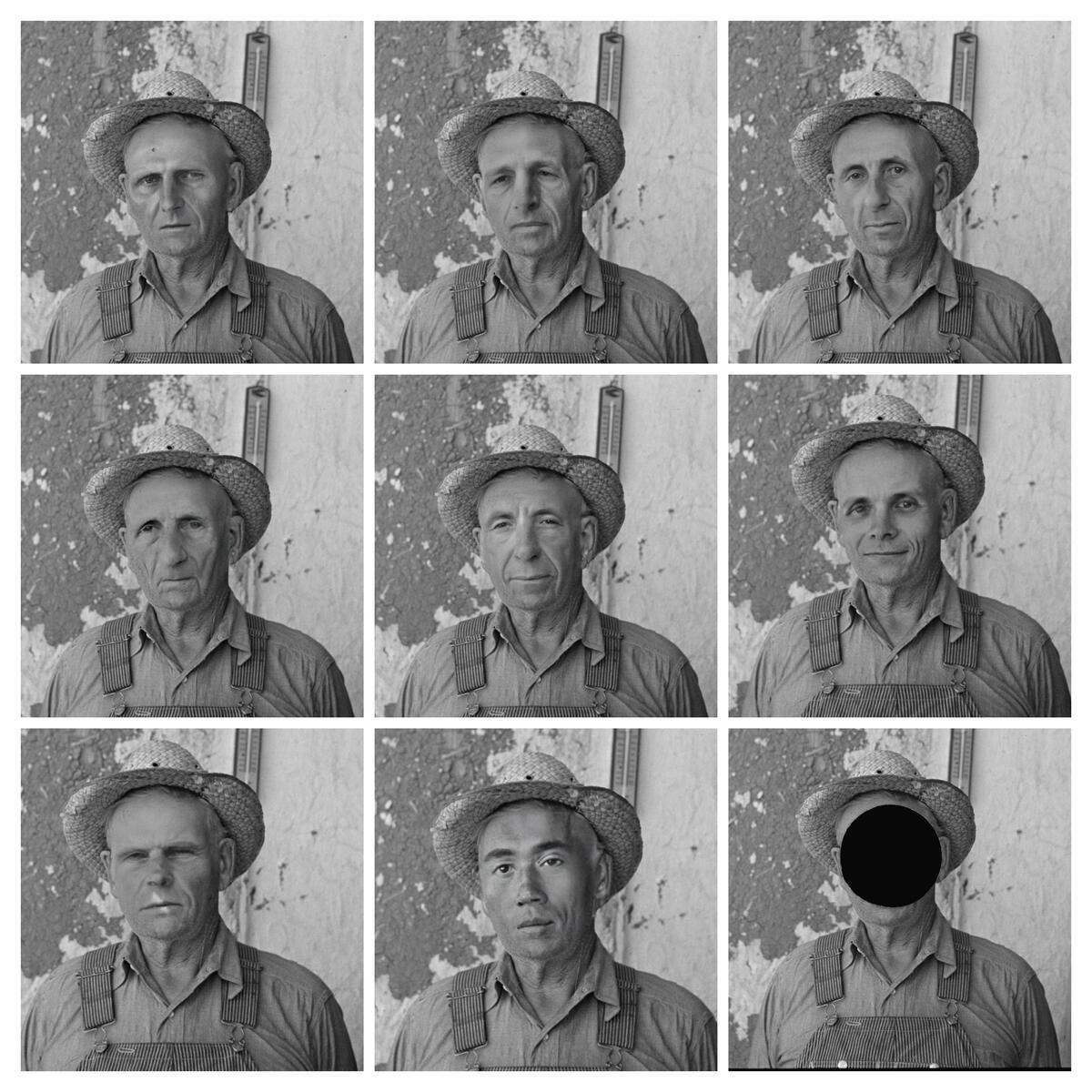

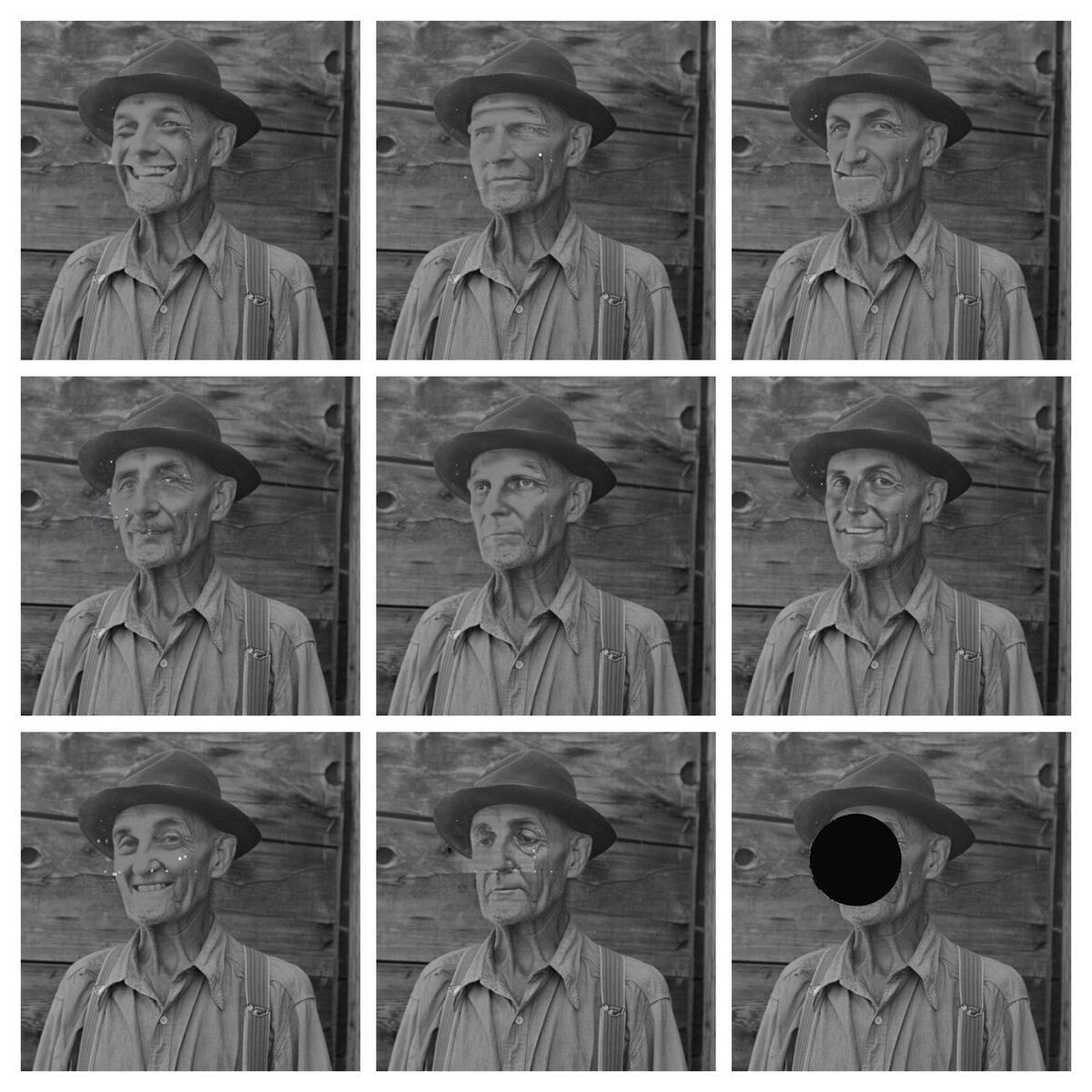

© Phil Hill, Rehabilitation Client, 2023

"Vi er tilbake på det punktet der teknologi vil skape et paradigmeskifte i måten vi kommuniserer og konsumerer massemedier på, og setter spørsmålstegn ved ideer om «sannhet». FSA var et sterkt subjektivt dokumentarprosjekt, strengt kontrollert av redaktøren Roy Stryker som med et hull «tok livet av» negativer hvis de ikke passet inn i fortellingen. Jeg brukte AI for å «gjenopprette» fotografiet, og skapte en serie med generasjoner som manipulerer bildet. De nye versjonene blir en sammenfatning av hvordan AI-en mener fotografiet skal se ut basert på mine input."

- 1/1

© Phil Hill, Rehabilitation Client, 2023

"Mens vi fortsetter å kjempe med teknologiens innvirkning på livene våre og kunsten vår, er denne serien en del av en samtale om nye måter å reflektere over fotografiets kraft til å forme vår oppfatning av virkeligheten."

–Phill Hill

- 1/1

© Phil Hill, Rehabilitation Client, 2023

Her kan du lese Phil Hills prosjektbeskrivelse

Rehabilitation

Project description

The Farm security Administration (FSA) Photo File was created at a point in time where photography ‘was emerging fast as mass tool of mass communication’ (Tagg, 1988, p. 181). We are at that point again; where technology will create a phase shift in the way that we communicate and consume mass media, calling into question ideas of ‘truth.’

The FSA project can be compared to the rapid arrival of Artificial Intelligence (AI). As John Tagg notes: ‘the “truth” of these individual [FSA] photographs may be said to be a function of several intersecting discourses: that of government departments, that of journalism, more especially documentarism, and that of aesthetics […] a composite picture of rural America in the late 1930s and early 1940s, conceived by apparently one man but called into being, administered and employed by specific government agencies’ (1988, p. 173).

FSA was a heavily subjective documentary project, strictly controlled by its editor Roy Stryker who ‘Killed’ negatives if they did not suit the narrative, with a hole punch.

I used AI to ‘restore’ the photograph, creating a series of ‘generations’ that retouch the image drawing from a ‘composite’ of what the AI believes the photograph should look like based on my input. Each generation is imposed on the archive image subtly, and others not so subtle but each different from the next.

Through my use of AI, I highlight the ways in which this technology can be both a tool for creativity and a potential threat to authenticity in photography. This work speaks to larger issues around representation, manipulation, and the ethics of image-making in the 21st century. As we continue to grapple with the impact of technology on our lives and our art, this series is part of a conversation in new ways of thinking about the power of photography to shape our perceptions of reality.