Marie & Bolette + Paulina - Summary

The suffragettes and photographers Marie Høeg (1866–1949) and Bolette Berg (1872–1944) ran the photography studio Berg & Høeg in Horten from 1895 to 1903. In 1980s a number of glass negatives of their work were found and donated to Preus Museum. The discovery included two boxes labelled “private”, and it is these boxes that have aroused the most interest. The pictures in the boxes show the two of them playing around with gender roles and challenging the conventions of portraiture in their studio. The photographs have won international acclaim, especially in queer communities that do not have that many historical models to look up to. The pictures will serve as the basis of Preus Museum’s contribution to the Year of Queer Culture, namely the exhibition Over the Rainbow, which will open at the museum on 28 May with Hilde Herming as curator. Marie & Bolette + Paulina will be mounted outdoors and unveiled at the same time.

How to carry out the commission?

When Tamara received the commission, she began thinking about how to carry it out: “My first instinct was to hesitate,” she recalls. “For what could little old me do with these ‘big’ historical pictures? When I received the photos that I could choose among, I saw that they were already perfect just the way they were. Marie and Bolette were excellent and trained photographers, and it was difficult to do it easily. This is not a question of innovative art, but about reproducing something that is already important in a historical context and showing it in a new light.”

What was the best way for their world and Paulina’s world to meet: should they come to her, or should she come to them? The result was that they met somewhere in the middle – neither here nor there, but a kind of new dimension. All the while with a playfulness and lightness amid the seriousness, and all the while with the overriding question: Would Marie and Bolette have liked it?

Queer models and “gaydar”

Paulina came across Berg & Høeg’s pictures already at photography school, and for her as a queer woman the pictures have a great historical value. When working with the pictures, she asked herself whether she could really know that the two ladies were queer. To be sure, they did live together their whole life, but there are no known letters or diaries that they left behind. Marie in particular was a well-known suffragette and women’s rights activist, but we know little about Bolette. And it was not unheard of at that time for unmarried women to live together. Is it just an unfounded claim that they lived together as romantic partners? Or did Paulina get a queer vibe from them?

Paulina explains that the concept of “gaydar” refers to how there is a special energy between queer people, where a certain look or tone sets your “alarm” off, or at least makes you more attentive. According to Paulina, “The more I came to know Marie and Bolette, the more I was able to confirm that they are like me. The reason it all rang a bell for me was that we wanted to query forced gender roles. It’s not so much about sexual orientation, but about gender roles and how you relate to them. But that is of course what queerness is also about – it’s about deviating from the norm, from the standard. And it’s still demanding to be a woman today, perhaps especially for those who challenge and explore current norms.”

Outside the framework

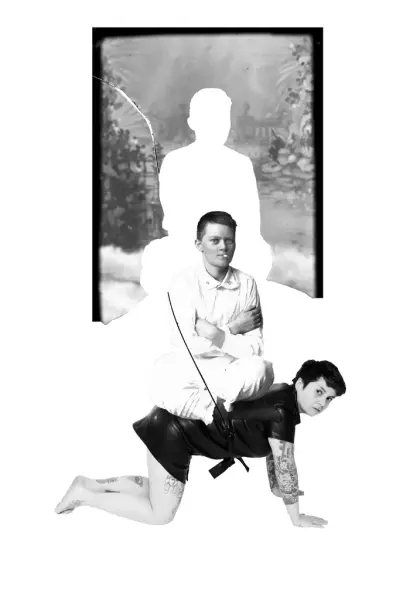

Paulina had to literally think outside the normal framework. Photo frames may feel rigid, both in a physical and a metaphorical sense. Paulina wanted to challenge and break the frame, not only physically, but also by turning it into something bigger by using the queer framework to her advantage.

As was the case with Marie and Bolette, Paulina’s pictures were taken in a private setting, in a studio. There, she is also allowed to challenge things without being observed – it all takes place in a secure environment, with the studio as a “safe space”. She can control the outcome afterwards to a certain degree by choosing what is to be shown or not. She also used pictures that are not personally flattering, with her philosophy being that the pictures refer to something that is bigger and more important than her ego.

A moral compass

As mentioned above, Marie and Bolette’s pictures were hidden away in a box labelled “private”. Is it then okay to show the pictures in public? Is it okay to play around with them, to alter them? The museum advised Paulina to just use her moral compass, prompting her to wonder what exactly a moral compass is, and who makes it. And moral compass in relation to what?

“I’m a rebel myself, so usually when someone says ‘no’, I want to automatically say ‘yes’,” Paulina explains. “Sure, it’s all a bit childish, but I think being childish is absolutely vital. Life ends sooner when you stop being childish. And for me as a queer woman it is important that the pictures are made public, for the sake of the queer narrative and the historical models.”

About Paulina Tamara

Paulina Tamara is a Bergen-based artist and photographer with a master’s degree from the University for the Creative Arts (UCA) in London. Through her pictures she mainly explores identity and (queer) culture. She has exhibited her pictures at museums and at several of Norway’s contemporary art galleries, taking for example part in the exhibition Skeivt uteliv (“Queer Clubbing”) at the Museum of Cultural History in Oslo during Oslo Pride in 2017. The exhibition was also shown at the University Museum of Bergen during the Rainbow Days festival in Bergen in 2018. Paulina has an ever-expanding archival project where she portrays the queer community in Norway in her series The Others, which is also being shown at the Over the Rainbow exhibition at Preus Museum. She has recently also begun engaging in a performative practice that explores gender roles and sexuality.