Edward Curtis - Summary

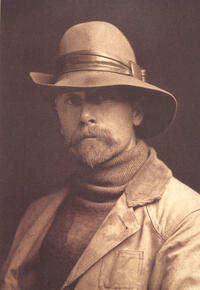

The finest portrait photographer in Seattle

There is little to suggest that Edward Sheriff Curtis (1868–1952), who was born in Whitewater, Wisconsin, and grew up in Cordova, Minnesota, had extensive contact with Native American tribes during his formative years. His only knowledge of the indigenous population was presumably the tales of them he was acquainted with from the press and popular culture. Even so, at the age of thirty-two he ended up embarking on the great journey of his life, with a single goal in mind: to document the indigenous peoples of North America.

A new vein of photography

Two chance encounters would radically influence Curtis’s life. First, in 1895, the celebrated portrait photographer, who made his living by eternalizing the citizens of Seattle, took a series of photographs of Princess Angeline, the eldest daughter of Chief Seattle. These pictures led to a national breakthrough, and this recognition led Curtis into a new vein of photography. Then a few years later, on one of his many trips, Curtis saved a group of researchers who had gotten lost in the mountains near Mount Rainier. One of these researchers was the anthropologist George Bird Grinnell. Grinnell became a close friend and was Curtis’s mentor on his first official expedition to Alaska in 1899. This expedition, organized and led by the American railway magnate Edward Harriman, was regarded as the largest such venture of the era.

A year after the Harriman expedition, Grinnell invited Curtis to the Piegan reservation in Montana. The two journeyed together to be present at what was presumed to be the very last time the Blackfoot Confederacy would perform the Sun Dance ritual. Both the ritual and the encounter with the indigenous people made a deep impression on Curtis, prompting him to conceive of a major photographic documentation project that aimed to record the Native American population’s way of life before it was supplanted by more modern lifestyles. The same year Curtis led the first of many expeditions where, accompanied by several assistants and scientific collaborators, he began the extensive work of documenting the diverse ways of life of the North American tribes.

Through his network of acquaintances and his newfound reputation as a skilled photographer, Curtis managed to attract sponsors to back an extensive book project. In 1906 he secured a deal with the financer and banker John Pierpont Morgan, who granted Curtis a stipend of $75,000 in order for him to deliver the finished product within five years. As the story goes, Morgan, after having been persuaded to participate, wrote to Curtis that “I want to see these photographs in books – the most beautiful set of books ever published”. As the primary sponsor, Morgan would receive twenty-five sets of the book series and five hundred original photographs.

The first volume was published in 1907 and focuses on the Apache, Jicarilla, and Navaho tribes. The fact that the preface was written by none other than President Theodore Roosevelt testifies to the prestige that Curtis’s project enjoyed in the beginning. However, over two decades would elapse before the final two instalments of the twenty-volume series would see the light of day.

«Kill the Indian, and Save the Man»

One of the signature photographs from the first volume is titled The Vanishing Race (1904). The choice of title and subject matter was not coincidental: the small band of people from the Navajo tribe riding into a blurry landscape symbolizes how the condition of the indigenous population was commonly perceived at the time. Ever since the Europeans landed on the American continent, there were constant conflicts between the native tribes and the new colonial masters. This was a conflict that over the centuries led to the large-scale loss of both human life and precious resources. It has been estimated that epidemics that were brought to the country by Europeans, as well as wars and skirmishes with settlers, reduced the population of certain tribes by as a much as 90 per cent.

In the late 1800s, the official American policy was that the native population was to be assimilated, under the motto “kill the Indian, and save the man”. One of the measures was to ban the public performance of religious rituals. Many natives were also forcibly relocated from their ancestral homelands, and many tribes were coerced into reservations. There was a deliberate policy of inducing the tribes to abandon their culture and their own language. Many children were therefore separated from their parents and placed in boarding schools. The goal was to tame the “savage Indian” and educate him to become a good, civilized citizen of the modern America.