Photo: Christine Wendelborg/Preus Museum

A bright idea

It is nearly impossible for us to understand just how revolutionary the invention of the photograph was: finally, people could preserve an exact image of how something or someone. By using a camera obscura, it had already been possible to see a picture – the challenge was to capture it. Many inventors took part in the race to be the first to develop a method that could retain the image that the light created. On 19 August 1839, victory was claimed by the Frenchman Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre (1787–1851). The date is now known as the birthday of the photograph – the day that the daguerreotype was gifted to the world. In his efforts, Daguerre collaborated with another Frenchman, Joseph Nicéphore Niépce (1765–1833), who sadly died several years before the invention was completed.

The daguerreotype is a silver-plated, mirror-like copperplate that is exposed to light in a camera. The picture is a direct positive, and it will be laterally reversed and appear as a mirror image (something that could be avoided by photographing through a mirror). Since the daguerreotype is made on an opaque plate, there is only a single copy of each picture.

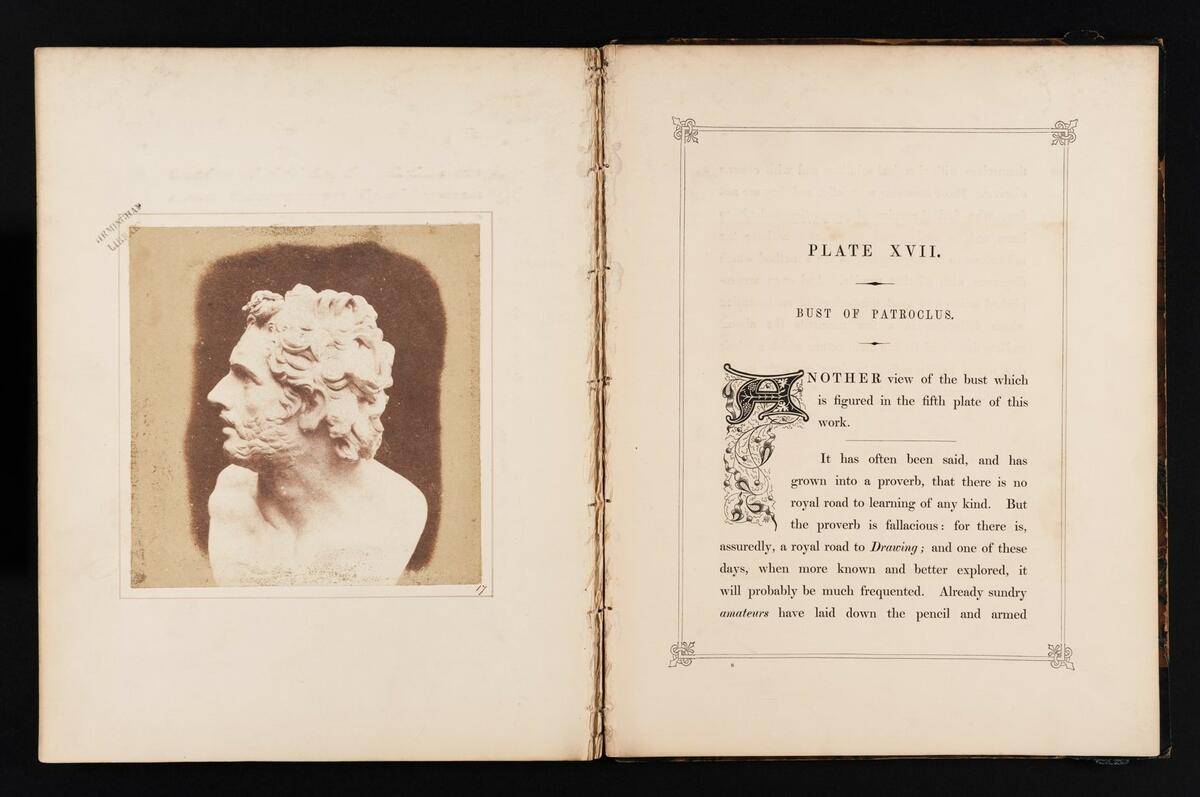

A brighter idea

The daguerreotypes were exclusive – each time a photograph was taken, only a single copy was created. How could numerous copies be made?

Did you know that Norway had its own photography pioneer? Not long after Daguerre and Talbot documented their processes, Hans Thøger Winther (1786–1851) published Norway’s (and one of the world’s) first photographic books explaining his three different methods of photographic reproduction in 1845.

- 1/1

The Pencil of Nature, William Henry Fox Talbot, 1844. Preus Museum collection. (photo: Andreas Harvik/Preus Museum)

Clear as glass

Taking photographs on glass combined the best of the two processes: the sharpness and detailed imagery of Daguerre’s mirror, and the possibility of reduplication inherent in Talbot’s paper.

Wet plates, also known as collodion wet plates, were introduced in 1851 by Frederick Scott Archer (1813–57). As the name suggests, the plates had to be wet, or actually sticky, during the photographing and development phases. For that reason, photographers used portable darkroom “tents”. The wet plates afforded detailed and finely nuanced pictures. A modification of the process, where an underexposed negative was given a reverse side of black paper or velvet, became highly popular in the latter half of the nineteenth century. Such pictures were usually called ambrotypes. Ferrotypes were a less expensive variant on metal plates.

The photographer’s world became easier when the dry plate was introduced in 1871. All that was required was to put the plate in the camera without further ado, and it could be developed when it suited the photographer. The disadvantage was that the glass was still heavy and fragile.

«The Kodak» ble patentert den 4. september 1888, og skulle gjøre det mulig for folk uten teknisk kompetanse å ta bilder og skape minner for livet. Preus museums samling. Image from digitaltmuseum.org

Simple? Super? Spontaneous!

A revolution in a little brown box: George Eastman introduced the first Kodak roll-film camera in 1888. The initial version used paper, with a transparent base being introduced the following year. This made photography much easier and less expensive, so that it gradually became a hobby for “everyone”. This would fundamentally change our relationship with photography. Kodak’s motto was “You press the button – we do the rest”. After a hundred exposures, you sent your camera back to the factory, which developed the film and loaded the camera with a new roll of film. Since the camera was small and easy to use, people could take it along with them everywhere. This created entirely new types of pictures that were no longer staged and stiff, but more immediate and spontaneous.

Fast pictures

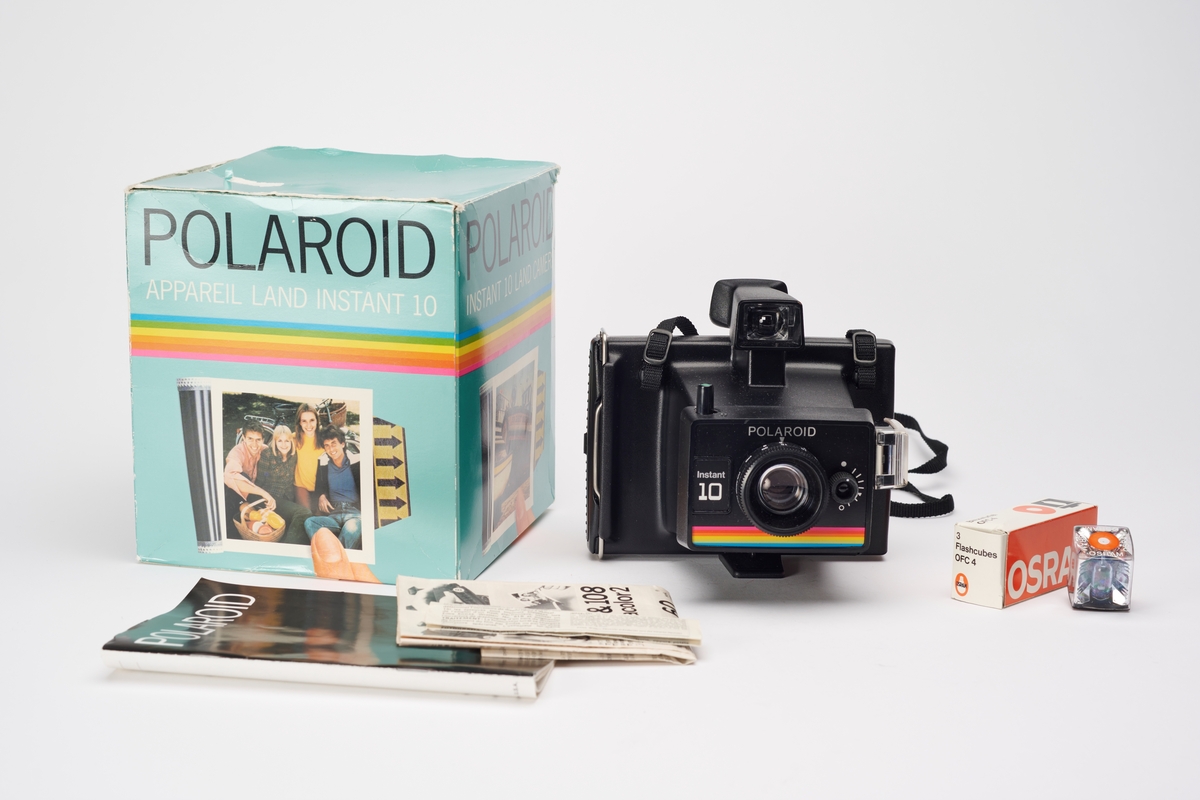

In 1943 a three-year old asked his father, Edwin Land, why they couldn’t immediately see the photo that had been taken by the camera. The question resulted in the first Polaroid camera in 1948, a fairly heavy contraption that produced sepia-toned pictures in a minute. This was followed by numerous other Polaroid cameras, and the Polaroid company was the world’s most cutting-edge technology company from the 1950s to the 1970s, becoming a veritable innovation machine that churned out one irresistible product after the other. During the 1970s, a billion instant photos a year were taken. Polaroid was not alone in the field, and several other camera manufacturers latched onto the instant photo trend.

The innovating continued, and the need for even faster photos resulted in the first digital cameras being launched in the 1980s. In a digital camera it is the image sensor that captures the light that comes in through the lens. This sensor replaces the film used in analogue cameras. The larger the sensor, the more detailed the digital picture.

In 2002 Nokia launched one of the first mobile phones with a built-in camera. The camera phone’s great advantage is that it is readily available and provides unlimited editing and sharing possibilities. The quality has also gradually improved – perhaps even to such a level that it’s only die-hard aficionados who see the need for cameras that can only take pictures?

Already by 2012, more pictures were being taken every single minute than in the entire nineteenth century combined. The current estimate is that around two trillion pictures are taken each year.

People really love to photograph!

- 1/1

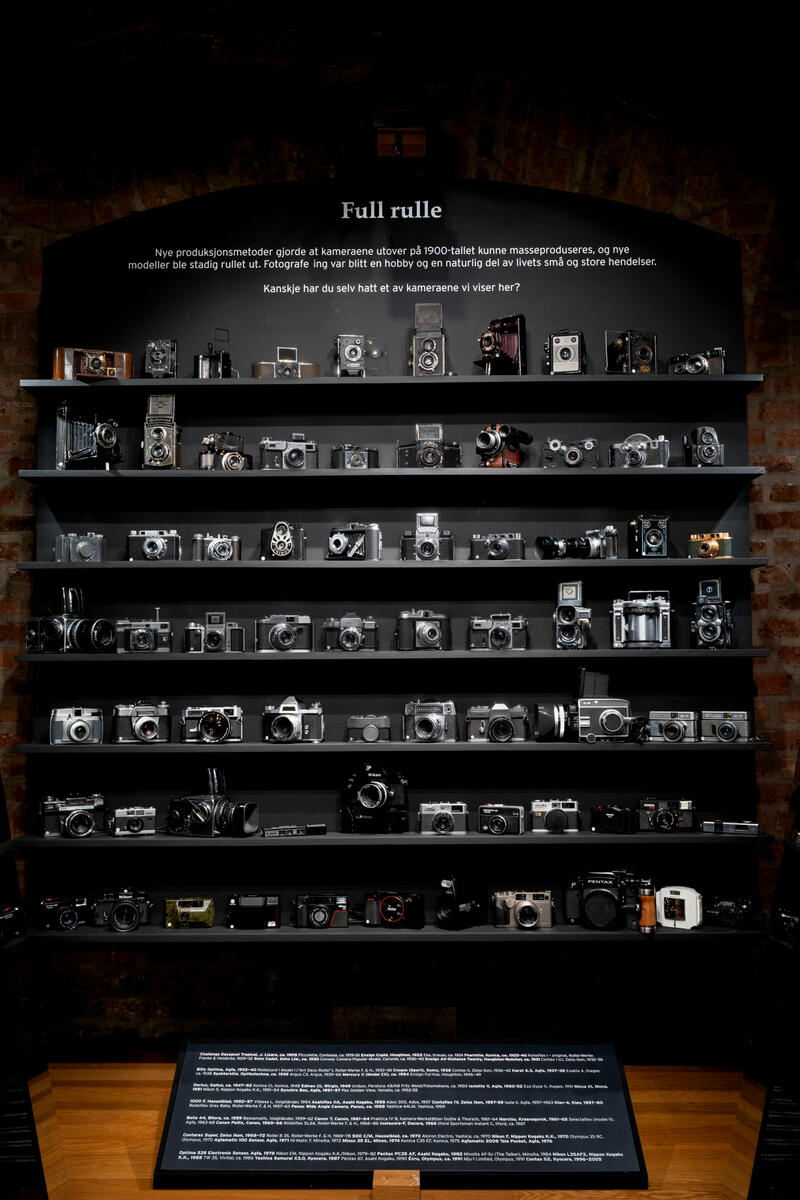

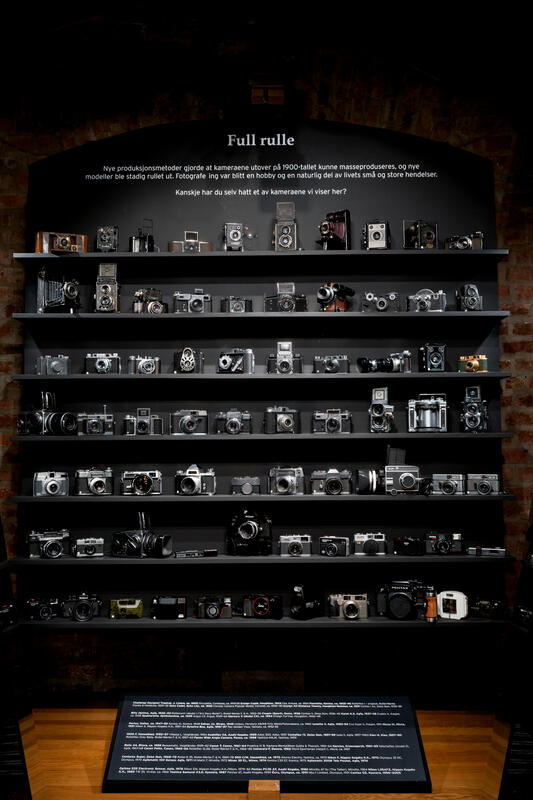

A few of the cameras in the Preus Museum's collection that have seen some of the world's small and large events. And clouds. (photo: Ana Goncalves. Animasjon: Ingri Østerholt)